The differences between compassion & empathy

and how learning this helped me navigate burnout

Learning the differences between compassion & empathy is one of the lessons that made me continue diving into compassion education. It rattled my brain and made the reasons behind my feelings of failure, burnout, shame, guilt, imposter syndrome, and helplessness all click into place.

Back before I started on this journey, I was waking up each morning feeling like the weight of the world had doubled overnight. It was 2020, and much of the year was spent inside my apartment, attempting to keep myself and others safe from a pandemic that was full of unknowns. The sky was red with smoke from some of the worst wildfires we've ever experienced here in California. We witnessed continued systemic racism and went to the streets in our masks, demanding change. The political climate was (and still is) full of divisiveness, hate, and violence. My feelings were laden with guilt, as I, a privileged white woman, am not the one suffering the worst consequences these situations create.

I asked myself the question, "how am I supposed to help enact change when I can barely get out of bed?"

This feeling of utter helplessness was what got me thinking…

How can I be present without letting it drown me? How can I be resilient when it feels like there’s additional suffering taking place in the world every time I turn around? How can I stay motivated to help, even when it seems like there’s nothing I can do?

This is where the differences between compassion and empathy come into play.

So, what are the differences between empathy and compassion?

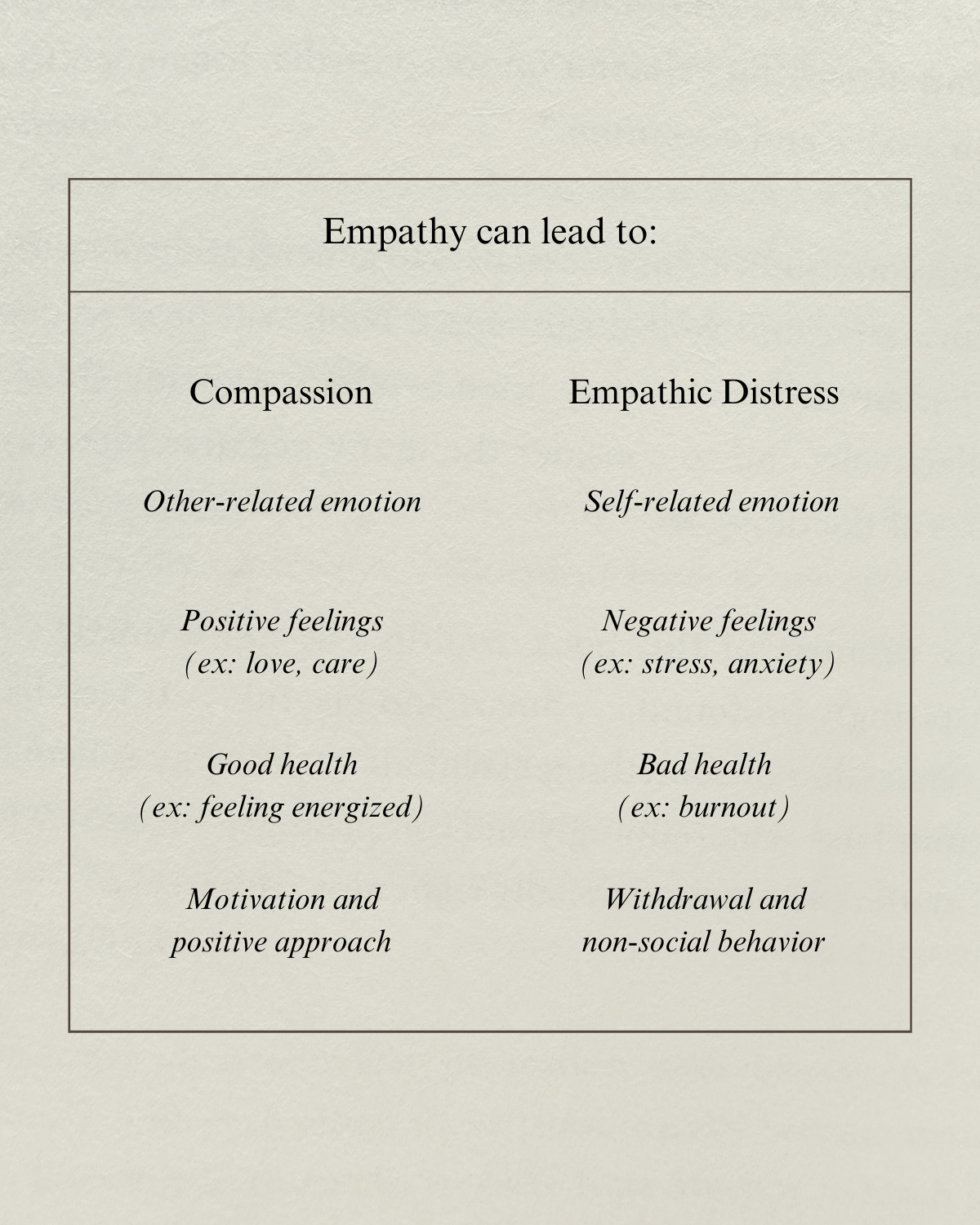

Let’s start with empathy. Empathy involves feeling another person's emotional experience as if it were one's own. It is the general capacity to resonate with the feelings of another, including both the positive and the negative. Feeling another person's negative emotional experience may lead to empathic distress, a self-oriented response to suffering, which we will explore further later on. It is often accompanied by disassociation to reduce one's own distress and protect oneself, which gets in the way of a compassionate response.

Compassion is the feeling of concern for another's suffering, accompanied by the motivation to help alleviate the suffering. It involves paying attention to the condition of others/ourselves/the world, being moved by the suffering we witness, feeling the desire to help relieve that suffering, and taking action to alleviate it. Compassion is other-oriented, feeling for instead of feeling with the other. This difference helps to drive action instead of withdrawal.

Compassion can also be considered an empowering choice we can make in relation to suffering. It moves us beyond feeling to active decision-making. (You can read more about compassion as a choice by my dear friend and mentor Monica, here)

Empathy is often unintentionally or automatically sharing the feelings of others, which includes both positive and negative emotions. Empathy can lead to compassion (a positive response that leads to action), or it can lead to empathic distress (a negative response that may lead to shutdown). Compassion is directly linked to suffering.

What is empathic distress?

The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science notes that exposing a person to suffering does not guarantee that person will react with compassion. The recognition of suffering can lead to other emotional states, including distress, anger, or even righteous satisfaction.

Multiple studies tied recognized suffering to empathic distress, a response in which one is more upset by the others' suffering than concerned for the other. Empathic distress is associated with efforts to reduce one's own anguish and interferes with the ability to respond with compassion.

Empathic distress may also promote indifference to others' suffering or lead to taking on the role of a "bystander," someone who adjusts their feelings to match a noncommittal stance when the suffering of another is too overwhelming.

The opposite is also true. Kelly McGonigal speaks of empathic distress leading to "pathological altruism" in her book, The Science of Compassion. This is when the action of helping is not rooted in compassion; it is just an attempt to escape or reduce one's own stress, guilt, discomfort, etc... A person will help others because they want to make themselves feel better. This can lead to unskillful behaviors like enabling or becoming a martyr.

For example, when I've felt my nervous system activate while reading the news or scrolling, being able to name where I'm feeling the tension in my body has helped me stay present, keeping myself from drowning in negative thoughts and ruminations. This presence gives me the space to ask myself if there is anything I can do in the moment to help or talk through what I'm witnessing with a close friend or loved one.

It is important to note that reacting with empathic distress is not a bad thing. It simply means you care and feel for what you are witnessing. Compassion and mindfulness practices are simply a way to move through that response so you are able to act instead of getting stuck in a negative cycle.

How can we move from empathy to compassion?

Experiencing painful or difficult emotions can often trigger thoughts that are self-critical and unhelpful. Thoughts like: When will this end? Why is this happening to me? I can’t handle this. What is wrong with me? Why does it feel like nothing is going right?

These types of thoughts take us out of the actual experience and can add to increased feelings of judgment, shame, or worthlessness if we believe them. These feelings can lead to further suffering.

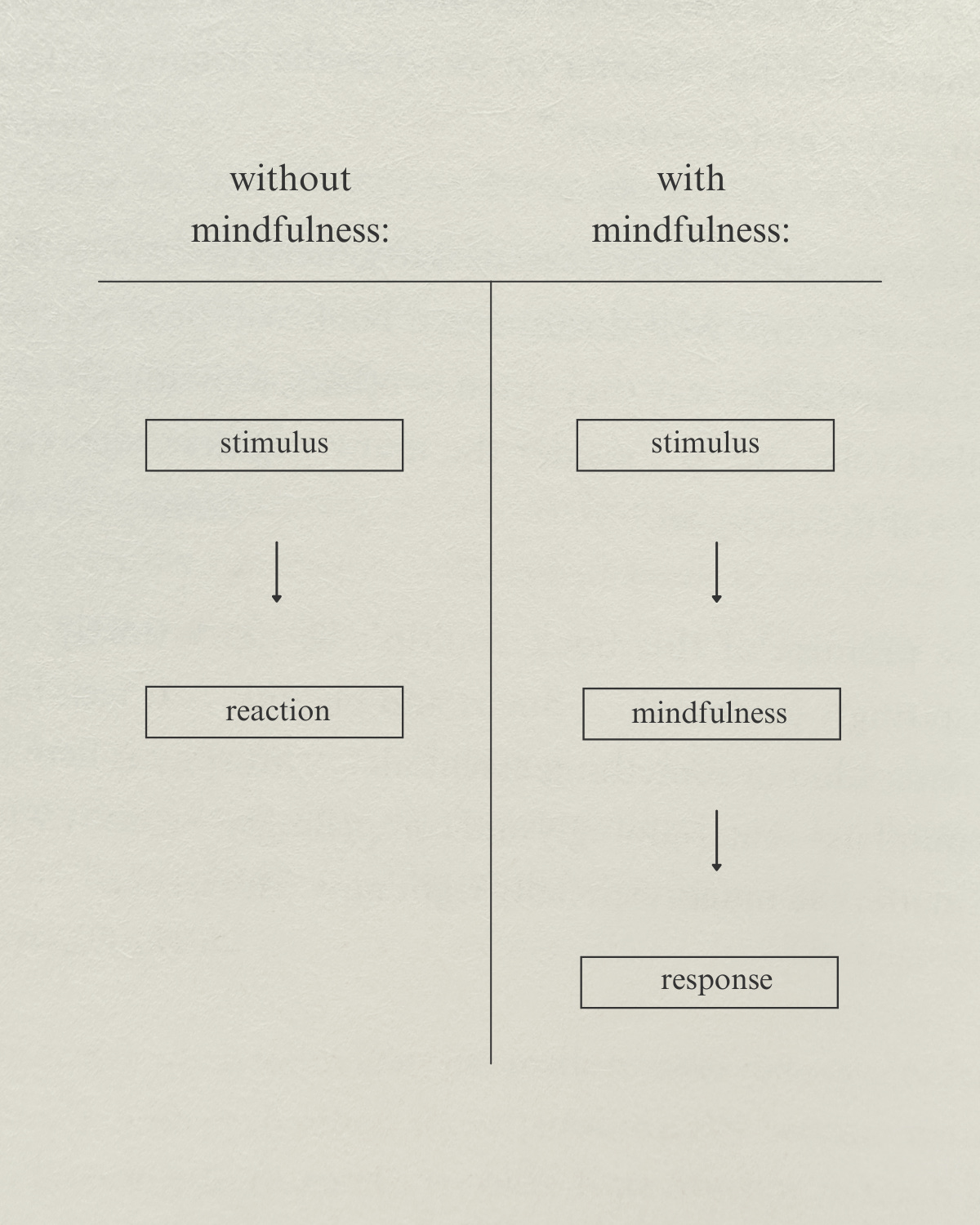

When we practice compassionate presence, thoughts naturally come and go in our minds, and we can label these thoughts as thoughts instead of treating them as facts.

The experience of pain and suffering is often perceived in our minds as “too much to bear.” With practice, we can trust in our capacity to meet with our direct experience within the context of each moment, sensation by sensation.

As we slow down and place our attention on the present moment sensations that occur in the body, we discover that we’re able to manage and bear emotions that, at first, seem too difficult to endure. The more we engage with this practice, the more our ‘muscle’ of being present with unpleasant sensations and emotions grows. Our capacity to meet these internal experiences in a sustained way is what allows compassion to arise.

The mind often thinks about the past, the future or makes up stories about the present. The mind is rarely in the present moment experience, whereas our body is always in the present moment. When we focus our awareness on the body, we’re naturally present in the here and now. The body is a natural anchor when we pay attention to it.

When we shift our focus from the initial emotions of pain, suffering, anger, sadness, fear, etc., and instead discover through curious exploration what is actually happening in the present moment in our body, we usually recognize that each individual moment is easier to turn towards and bear.

If you’re interested in practicing compassionate presence, here is a five-minute recording of mine you can listen to any time, which I learned during the Applied Compassion Training program at CCARE Stanford University.

Compassion Presence and Inquiry Practice:

If you’d like to do a written version of this practice, I’ve written the instructions below:

Think of an issue you would like to explore. When beginning this practice, try to bring up something moderate, not something overwhelmingly difficult.

Use some of the questions below to practice returning to the direct experience and staying present in the body:

What is the actual felt experience of the emotion you’re feeling? (sadness, anger, grief, fear, worthlessness, resistance, doubt, hopelessness, etc.)?

Where are you experiencing this emotion in the body right now? Where are the strongest sensations arising for you?

What are the physical sensations you are experiencing?

How is it to place your kind attention on these sensations?

What happens when you breathe into those sensations and allow them to be there?

What else do you notice as you rest with your experience?

Bring self-compassion into this experience.

How is it to bring your hand to that specific area as an additional compassionate presence for this experience?

How can you internally communicate to yourself that your feelings are allowed and accepted as they are? Here are some examples of ways you can speak to yourself with compassion:

I’m here with you. I support you. You belong. I’m listening.

To complete this practice, bring awareness to the sense of compassion that is already present whenever you meet suffering. Allowing oneself to feel this experience is a great act of compassion in itself. Take a few minutes to rest in this presence of compassion as a way to end this practice.

If you found this interesting and are curious about diving deeper and working with me 1-on-1, book a free consultation call. You can also click here to learn more about my coaching practice.

I help individuals who are feeling stuck, burnt out, and caught up in endless cycles of stress and self-criticism get unstuck using science-backed tools like neuroplasticity, self-compassion, nervous system regulation, and mindfulness (to name a few) to improve self-worth, move through imposter syndrome, further resilience, and create positive change in their lives.

I hope learning the differences between compassion and empathy has been as enlightening for you as it was for me. If you have any questions, please feel free to leave them in the comments or reach out to me at kristine@claggie.com.

Thanks so much for reading!